Lost in Translation? Compiling the Fiscal-Military System Bibliography

The fourth edition of the bibliography produced by the European Fiscal-Military Systems group was launched last month. It has, in total, a dozen languages; fifty headings and sub-headings; nearly two hundred pages; between two thousand and three thousand entries; just over sixty thousand words; and – according to MS Word – “too many spelling and grammatical errors to continue displaying them”. Though not anywhere near the level of the Bibliography of British and Irish History, which contains over 630,000 individual records, the bibliography nevertheless represents the largest single reference for the study of the fiscal-military history of early modern Europe and its colonies. Assembled as part of the process of researching the trajectory of the early modern European fiscal-military system, it has also been a chance for us, as a group, to reflect on the challenges of assembling a usable bibliography, and the nature of the wider scholarship on this topic.

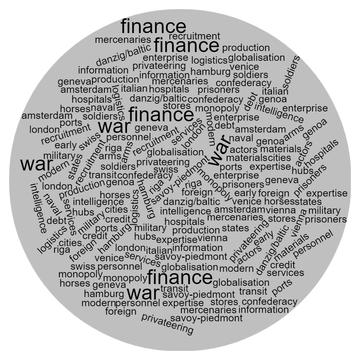

A significant problem, particularly for those of us working on political, socially or culturally fractured early modern regions such as the Baltic, Switzerland, Italy and the Balkans, is to chase and corral literature that is frequently scattered across a wide range of languages and fields. Keeping track of the Swiss Confederacy needs, for example, a knowledge of French, German, Italian and English, while a study of the famously polyglot Habsburg imperium in central and south-eastern Europe requires all these as well as Hungarian, Slovak, Czech, Serbian, Croatian, Romanian, and Polish. Though books on a specific place or topic in different languages do sometimes speak to each other, more often they speak to books written in the same language on other topics, resulting in significant lacunae in coverage until important concepts can jump the gap. The scholarship therefore reflects implicitly the academic networks and circles that guide research, the key figures who set the agendas in their respective fields, and the importance of scholars comfortable in several languages who can act as channels of communication between these overlapping but also still autonomous linguistic spheres.

Even once within these bodies of scholarship, we all encountered the further difficulties of searching. Some keywords make their way from one language to the other virtually unchanged, but others are lost in translation, making it inadvisable to rely on other bibliographies and requiring direct examination of the books, chapters or articles in question. Sometimes it’s necessary to follow authors instead of titles, or to rely on word of mouth. Differing academic conventions complicate the task even further. Whereas in most places textbooks are used mainly to synthesise existing research, we found that in Scandinavian historical practice they can also be used to present new research, making it necessary to incorporate them into the survey. At the same time, there is a stronger tradition there of publishing works aimed at a wider audience, frequently without footnotes or references, sometimes leading to dead ends when it came to tracking down the sources of broader conclusions. The process has therefore revealed the continuing diversity of what is often portrayed as an increasingly globalised, homogenised and deracinated academic community.

Even once the individual references have been assembled, there remains the issue of cataloguing them. Perhaps the ideal would be a fully digital database along the lines of the Bibliography of British and Irish History, drawn from the metadata of individual items, fully searchable by multiple keywords and providing links to online versions, but the commitment of resources that this would require is immense. And it would not address some of the basic challenges of categorisation. Some books or articles sprawl across multiple categories, both thematic and geographic, in ways that require excessive duplication. A book on the Baltic with multiple case studies, for instance, would appear in the sub-headings on Danzig, Hamburg and Riga as well as the Baltic heading. The same is true for early modern Italy, especially given the extensive overlap with Spanish, French, Imperial and Ottoman topics. Older narrative military histories, which often provide analysis of broader themes en train rather than in clear chapters, but which remain important references in the absence of more recent work, sometimes fit uncomfortably into the thematic categories we have chosen. It is a reminder that history is often an untidy story, that ideas and concepts cannot be reduced to neat conceptual boxes, and the need to be open to contributions even from literature not framed as ‘fiscal’ or ‘military’ in scope.

Like most historical scholarship, the bibliography therefore remains an incomplete and imperfect document, a work in progress, but one nevertheless more complete and perfect than before, and one that will hopefully provide other scholars with an introduction to the resources available for studying the early modern European fiscal-military system.

More information about the Bibliography and the download link can be found here.

Aaron Graham is the former Research Associate for the London case study, the European Fiscal-Military System 1530 - 1870.