Something Amiss at the Inn of Andrea Rovegno: A Story of Deserters and Recruiters at the Port of Genoa

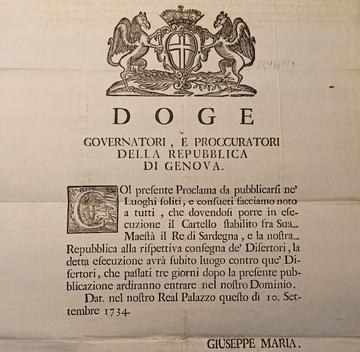

Proclamation of Genoese-Piedmontese Cartel of 1734

One night in late June 1734 six soldiers, two French and four Sardinian-Piedmontese, met at the Inn of Andrea Rovegno (Osteria d’Andrea Rovegno) in Genoa’s extramural, seaside suburb of Sampierdarena and hatched a plan. Their ploy (as best we can know from later police reports) was simple: the next morning, they would walk through the gates of Genoa, sell their uniforms and rifles somewhere near the Loggia della Mercanzia (one of the city’s chief markets), return to the suburb, desert their units, take a bounty from Spanish-Neapolitan recruiters (known as Ganci, literally ‘hooks’), board a Spanish ship, and sail to fight down in Naples. ‘The King of Sardinia…cannot prevent the recruits from being recruited in my house and being sent directly to our boats from the office,’ clucked Giovanni Agostino Carbonel, the Spanish comissario di guerra and asientista who almost certainly solicited the six men to join up.[i] If all went as planned, the whole scheme would take only a few days, and hopefully not arise the attention of any authorities, French, Piedmontese, or Genoese.

Such a plot, quite simply, should have been easy to stop. On the one hand, the kings of Spain, France, and Piedmont-Sardinia were allies. Nine months earlier, Philip V of Spain had united with the French court in support of Franco-Piedmontese efforts to return Stanisław I to the Polish throne, and promptly shipped out over 36,000 troops to Italy to fight in what came to be called the War of Polish Succession (1733-35). On the other, the Genoese were well aware that the city had become a haven for foreign soldiers and actively tried to stem the tide. ‘In the city at present there are a great quantity of foreigners, who live there without the usual pass/receipt…against regulations, as a great number of people who own osterie, rooms, and inns and are lodging [them]’ complained a proclamation posted at every lodging establishment around the city in late 1730, a period of peace and therefore of fewer foreign troops present.[i] Indeed, the Genoese had signed a formal arrangement, or cartel, a few months before the incident in Rovegno’s osteria agreeing to ‘immediately seize any French deserters in the City of Genoa, or in its suburbs of Sampierdarena, Bisagno, or in other places nearby [and] to immediately arrest them and imprison them in a secure place.’[ii]

Despite all these checks, however, the deserters had made off without a hitch, their scheme only coming to light a few days later because an anonymous source had tipped off the Piedmontese ambassador Castelli, who, in turn, alerted the French envoyè to Genoa, Jacques de Campredon (1672-1749).[i] Enraged, Campredon let loose on the Genoese, demanding they immediately search the suburb’s other lodgings for more deserters - the Inn of the Three Crowns (Osteria delle Tré Corone), the playhouse of M. Saluzza (Albergo di Spettanza del M. Saluzza), the osteria of the Black Eagle (L’Aquila Nera).[ii] Despite the cartel, Campredon fumed, deserters ‘enter freely from all parts in the cloths of servants, infantry, dragoons, and drummers, which disappear in a moment.’[iii] The Republic, Campredon went on, ‘had enrolled deserters of all nations both in the service of the Republic and for those of other Powers, to the exclusion of France alone...There are a great number of French deserters in Corsica, in the Palace Guards (Compagnie di Palazzo), and, in one word, everywhere.’ ‘In truth, these complaints would be easy for an Allobroge[iv] or a Chinese to understand,’ Campredon erupted, although ‘it would be difficult to make them understand how a Sovereign Republic knows so little how to oblige itself’ to the terms of the cartel.

The whole debacle – the deserters’ escape, Carbonel’s schemes, Campredon’s anger – sheds light on how Genoa’s spatial, institutional, legal, and regulatory environment shaped foreign recruitment and desertion in the city. As a substantial Mediterranean port and critical node in multiple logistics networks, Genoa had for a century struggled to manage the flow of licit and illicit military labor. Owing to a 1583 prohibition on foreign recruitment, army recruiters had largely ignored the city. This all changed, however, when the French bombardment of 1684 pried open Genoa’s closed military labor market. Over the next century, a rush of Spanish, French, and Piedmontese recruiters (and to a lesser extent their English, Dutch, Venetian, and Hospitaller counterparts) flooded into the city, suburbs, and Genovasato (Genoa’s countryside) to solicit, pay, and transport foreign military labor. At the same time, the numerous armies that crossed the Republic’s territory from 1684-1748 unleashed a counter-current of their own in the form of thousands of deserters.

Such circulations of military labor through Genoa raises a number of provocative questions. How could recruiters keep the supply of fresh troops flowing? In this so-called ‘age of deserters’ (Zeit der Deserteure), how could generals and diplomats prevent soldiers from slipping off of boats or skipping over the border and escaping into the port? How could Genoese public authorities simultaneously placate distant powers, recruit soldiers for their (admittedly small) army, and police their city?

I am currently in the middle of answering these questions for the most recent chapter of my upcoming book, Theater of Mars: Building the Business of War in Genoa, 1684-1797, a study of the business of war and urban space in the port of Genoa. The problem of desertion and recruitment in Genoa is particularly interesting to me. Beyond bringing the international politics of desertion to the forefront, approaching desertion and recruitment from the point of view of a fiscal-military hub presents a unique archival perspective on the military labor market missed in earlier, state-centric approaches. Consider that the six soldiers at the Osteria d’Andrea Rovegno would have presented themselves in dramatically different ways in the state records across Europe - these men disappeared as deserters from one archival record (either French or Piedmontese), appeared anew in another as recruits (Spanish), and, if caught, would have shown up as prisoners in a third (Genoese). Rather than viewing desertion as the end of a relationship between a state and a soldier and recruitment as the beginning of a new relationship between that same soldier and a new state, viewing military labor from the perspective of a fiscal-military hub exposes the multiple, overlapping forms of military labor, discipline, and surveillance present at one time and in one place.

Osetria del Botteghin on the Brenta (Giovanni Francesco Costa c.1750, Rijksmuseum)

Such an approach further places the market for military labor within the unique spatial context in which it actually operated. At a certain level, the often-confused urban landscape of a city like Genoa made it difficult for the Genoese authorities to accurately identify and surveil soldiers. But as I hope this chapter to show, Genoa’s authorities embarked on a deliberate campaign to better control recruitment and desertion through building large, purpose-built facilities to manage and quarantine new arrivals (lazaretto), expanding the city walls for protection and surveillance, and centralizing the accommodation industry through the registration of inns and hotels like the one owned by Andrea Rovengo. In this way, I hope to show how the early modern urban landscape funneled people in certain directions and mixed them in unexpected ways. That the deserters discussed above needed to sell their equipment inside the city walls and needed to be recruited outside these walls was not serendipity, but the result of deliberate policies. Only by viewing the military labor market through such a close, spatial lens can we hope to better understand its many complexities.

[i] ASG, AS, 2941, 1/7/1734. Avendo io.

[ii] ASG, AS, 2941, 7/7/1734. Avendo io Segre[tario].

[iii] ASG, AS, 2941, 8/7/1734. Memoria. Dopo che.

[iv] The ancient Gallic people between the Rhône and the Alps.

[i] ASG, AS, 2923, 11/1730. Magistrato della Consigna: ‘Presentendo detto Prestantissimo Magistrato essere nella presente Città...’

[ii] The cartel appears in multiple drafts in ASG, AS, 2940.

[i] Quoted in Cristina Borreguero Beltran, ‘The Spanish Army in Italy, 1734,’ War in History, 5 (1998), 412.

Michael Martoccio is Research Associate for The European Fiscal-Military System 1530-1870, and focuses on the Genoa case study.