Part II A profitable partnership: France and the Swiss Confederacy 1793 - 1813

Franco-Swiss relations were at a nadir in early 1793. The execution of Louis XVI in January shocked the Swiss, who – ironically – were long-standing champions of republicanism. However, they abhorred the lawlessness, confusion, and anarchy into which France had plummeted. The British foreign minister, Lord Grenville, hoped that it might be possible to interest the Swiss in an alliance against the new French republic, alongside Britain’s other partners in the First Coalition: Spain, the United Provinces, Savoy-Piedmont, Austria, and Prussia. Swiss troops, paid by Britain, would be used to invade France’s south-eastern provinces, in conjunction with a British naval attack on France’s Mediterranean ports, principally Toulon. However, Grenville’s natural caution led him to warn George III’s envoy in Switzerland, the Anglo-Irish aristocrat Lord Robert Fitzgerald, that he was not to commit the British government to any alliance with the Swiss without ensuring the co-operation of Austria. Fitzgerald himself was unimpressed with what he perceived as a general lack of Swiss military spirit, writing in June 1793:

"The [Swiss] people have now lost sight of their past injuries and their rulers grown old in ease and the enjoyment of peace; so far from seeming to rouse themselves again, [they] seem to value themselves upon their moderation and those concessions which have hitherto preserved this country from the aggression of France."

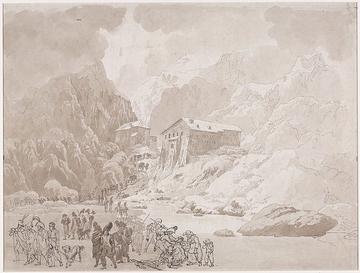

French troops crossing the Grand St Bernard in 1800

The French themselves recognised the threat that an allied army, attacking through Switzerland, might pose to the revolution’s security. To forestall any potential Austrian march through the Fricktal valley, the French general Custine constructed an enormous gun battery between the Rhine fortress of Huningen and the Swiss city of Basel, which inevitably provoked complaints from the federal Diet. The battery was demolished in May 1793 and Custine expressed his anger at the Swiss failure to object in like manner to those constructed by the Austrians on the far side of the Rhine. In French eyes, Swiss neutrality was fictitious at best. Nonetheless, François de Barthelemy, the republic’s ambassador to the Swiss Diet, recognised Swiss co-operation in allowing horses, cattle, and pigs to be exported from Switzerland for the use of the French army. France, feeling the pinch of hunger due to continued war, poor harvests, and currency inflation, was heavily dependent on supplies of food from beyond its frontiers. Swiss merchants, and the cantonal elites, were all too happy to profit from their powerful neighbour’s needs.

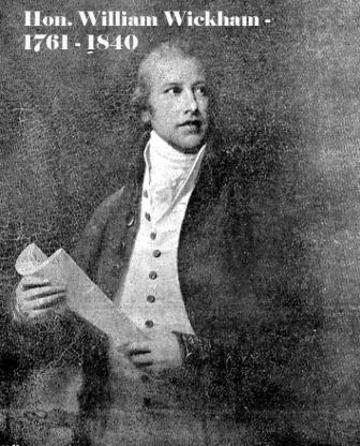

This dependence upon the Swiss – as a neutral, agricultural neighbour – gave rise to covetousness. French revolutionary ideals had already seeped into the Confederacy, stimulating unrest in the Pays de Vaud, where the writings of an exiled lawyer and academic, Frédéric-César de La Harpe, proved influential. A Jacobin-inspired uprising at Geneva in December 1792 – following an abortive attempt by French troops to seize the city – also alarmed the conservative elites in the Swiss cantons, as well as the major powers of Europe who were united in their opposition to French radicalism. The idealistic Oxford graduate William Wickham, appointed as Fitzgerald’s successor in 1795, established an intricate network of royalist agents in the Swiss Confederacy which he used to infiltrate France and stimulate counter-revolutionary activities. Wickham’s espionage was no secret from the French, who successfully pressurised the Diet to expel him.

Even after the collapse of the Committee of Public Safety and the eclipse of Robespierre in 1794, French designs on Switzerland, as a source of food and a troop depot, remained vivid. The Directory drafted plans for a French annexation of Switzerland late in 1797, and a French army invaded through the Vaud early in the spring of 1798, meeting little resistance until it reached the canton of Bern. A French victory over Bernese forces at the battle of Grauholz in early March spelt the end of Swiss self-determination and neutrality, and a nominally independent Helvetic Republic was proclaimed, governed by a Directoire helvètique. Geneva was also conquered and annexed by the French, and became the mere capital of a newly-created Département de Léman, losing the sense of republican liberty and sovereignty it had enjoyed since the 1530s. The occupying French forces treated Switzerland as a hostile zone to be plundered ad lib, thereby undermining the authority of the new French-sponsored centralised republican state, and ensuring that a form of civil war raged throughout the country until 1802.

Suvorov at St Gotthard (Wikimedia)

More significantly, France’s attack on the Swiss was considered a breach of the spirit of the Treaty of Campo Formio, which had ended the War of the First Coalition in October 1797. The War of the Second Coalition saw Austrian and Russian troops – backed by British subsidies – attack French conquests in Italy and Switzerland, only to fail on both fronts after the campaigns of 1799 and 1800. After initial setbacks for France in both theatres, André Massena defeated an Austro-Russian force under Alexander Korsakov. at the second battle of Zurich in September 1799. The famous fighting withdrawal of Korsakov’s compatriot Suvorov through the Alps into Germany, to escape encirclement by the French, was a small but gallant success in the face of disaster. Allied efforts to end the French occupation of Switzerland had failed. In May of the following year, 1800, the new First Consul of France, Napoleon Bonaparte, led his own forced march via Geneva through the French and Italian Alps into Lombardy, and defeated the Austrians at Marengo with his Armée de Reserve.

Peace between France and Austria in 1802 resulted in France’s withdrawal from the Helvetic Republic; however, the regime collapsed into civil war later that year, necessitating the rapid return of French troops. Napoleon, working through General Ney, imposed an Act of Mediation in 1803, which partially restored federalism in Switzerland. This was accompanied by a troop capitulation, specifying that the Helvetic Republic was required to provide France with four regiments, totalling 16,000 men. Bonaparte had emphasised that he would not seek to “chain the children of Tell” by continuing French domination of their country. But to all intents and purposes, Switzerland was a French client for the next ten years: Swiss commerce with its traditional trading partner, Britain, suffered severely due to the Continental System; and Geneva (as capital of a French département) was compelled to supply conscripts to the Grande Armée. It was not until Napoleon’s power leached away in the months after the Battle of Leipzig in 1813 that some degree of normality would return. Part III of this blog series will assess the beginnings of a new era in relations between the French and Swiss, born out of the confusion and uncertainty of 1814-15.

John Condren is Research Associate (Geneva case study) for The European Fiscal-Military System project. Email john.condren@history.ox.ac.uk