A profitable partnership: France and the Swiss Confederacy

Part I: 1715 – 1792

In the spring of 1715, Louis XIV of France, an aging king with entrenched ultra-Catholic views and ruling a militarily and financially exhausted kingdom, authorised the signing of a new alliance with Bourbon France’s traditional confederates, the Swiss. This procedure followed the established method whereby each canton sent one or two delegates to negotiate jointly with the French ambassador to the Swiss Confederacy. This agreement differed from previous treaties with the Corps helvètique, however. Louis was willing only to countenance a treaty with the seven Catholic cantons. This was due largely to his suspicions of their Protestant counterparts, most especially Bern, the most powerful canton in the whole Swiss Confederacy.

In 1712, a short religious and civil war between the Protestants and Catholics – the Second War of Villmergen – had destabilised Switzerland and resulted in a Protestant victory. As a price of the new agreements for the levying in their territories of troupes étrangères for the French army, Louis demanded that land conceded to the Protestant cantons be restored to the Catholics: a condition which Bern refused. As a form of punishment, they and the other Protestant cantons were thereby excluded from the extensive system of patronage which accompanied Franco-Swiss treaties throughout the Ancien Régime. Furthermore, a secret clause to the 1715 treaty committed France in vague but provocative terms to support the Catholic Swiss in the restoration of the Roman faith in the Confederacy at some unspecified future date. The text of this secret clause was hidden in a trunk in the state archives of Lucerne, hence the agreement’s epithet of the Trücklibund.

France’s preference for the Catholic cantons – Lucerne, Fribourg, Solothurn, Uri, Schwyz, Upper and Lower Unterwald, Zug, and the Catholic areas of the bi-religious cantons of Glarus and Appenzell – echoed that of the Spanish and Savoyards in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These two latter powers had generally confined their recruitment among the Swiss to the territories of the rural Catholic cantons. Their Protestant equivalents, of whom the most powerful were Bern, Basel, and Zurich, had received overtures from the British and Dutch during the recent War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714). But the fact remained that France was the most influential neighbour the Swiss possessed, even despite the increase in recruitment for the Dutch army among the Protestant cantons in the eighteenth century. Ever since the first formal troop convention between France and the Swiss Confederacy had been signed in 1521, Swiss soldiers had received incomparable opportunity to distinguish themselves in the service of a foreign monarch. They were prized for their toughness, discipline, and fighting ability, and their privileges – including, where applicable, the right to worship as Protestants - were generally respected, though with certain caveats. This latter aspect is currently being investigated in different contexts by Paul Vo-Ha and Scott Sowerby.

France’s proximity to Switzerland meant that many Swiss merchants considered the French kingdom their principal marketplace, especially cities such as Strasbourg, Dijon, and Lyon. This was reflected in the privileges traditionally granted to these merchants within France as part of the military alliances agreed between 1516 and 1816. Artisans were allowed to practice their industry “en toute liberté”, while Swiss and Genevans residing in the kingdom were generally excluded from the droit d’aubaine: the king’s right to the possession of a foreigner’s property in France upon the death of that foreigner. As Peter Sahlins points out, over 50% of naturalised Swiss in eighteenth-century France were Catholic priests, which emphasises the transnational religious connections between France and the Corps helvètique. In an economic context, supplies of salt from France (especially Languedoc and the Franche-Comté) were crucial for Switzerland, which produced little of its own, and again these were tied into agreements with the French monarchy for the provision of soldiers.

Moreover, French pensions to the élites of the Catholic cantons – as rewards for their support – contributed to an undercurrent of instability in Switzerland after 1715. This manifested itself in the Durs et Doux unrest at Zug in 1729, when the Zurlauben family’s control of the salt monopoly and the recruitment payments from France was challenged by other prominent families within the canton. The situation was not completely resolved until 1768. By virtue of its patron-client relationship with the Swiss, France also assumed for itself the role of peacemaker in civic urban conflicts and regularly intervened to quell discord in the Confederacy. This extended to involvement in the affairs of neutral and independent states which were nonetheless closely allied to the Swiss: in 1738 the comte de Lautrec, Louis XV’s envoy extraordinary to the tiny Republic of Geneva, mediated a resolution to political upheaval in that city, which was not at that time a full and formal member of the Corps helvètique.

Swiss troops had been prominent in France’s military successes in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), perhaps most noticeably at the Battle of Fontenoy. But in the years subsequent, and especially after the Seven Years War (1756-1763), Louis XV and his ministers embarked on a series of cost-cutting measures and reorganised the terms of France’s capitulations with the Swiss cantons individually and collectively. Among the more significant changes was a proposal that captains would no longer assume proprietary rights over the companies they commanded. In 1764, for instance, delegates from Fribourg tried to ensure that as many as possible of the 15 companies the canton “possessed” in French service were commanded by officers from the canton. Despite the unpopularity of the French reforms – which the comte de Beauteville, French ambassador to the Confederacy, reported on extensively – a new military capitulation was negotiated with the Catholic cantons and the allied territory of the abbot of St Gallen in 1764.

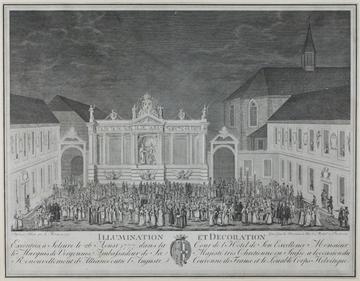

In 1777, after the death of Louis XV, the Franco-Swiss alliance was renewed in pomp and splendour at Solothurn, arguably the most Francophile of the cantons and the city where the ambassador traditionally resided. This new agreement reincorporated the Protestant cantons, and the Trücklibund was implicitly annulled.

The young Louis XVI also guaranteed Swiss independence and neutrality – this was important, given that Europe had recently witnessed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth being carved up and divided among Austria, Russia, and Prussia. This occurrence had alarmed the Confederacy, which was not a formal state with centralised political machinery, but was instead rather loosely held together by vague ideals of being “Swiss”.

Moreover, the French secretary of state for foreign affairs, the comte de Vergennes, was unwilling to tolerate any changes to the status quo on France’s eastern frontiers. In 1782, French troops united with those of Bern and Savoy-Sardinia to quash a serious revolution at Geneva against the authority of that city’s conservative, oligarchical, and allegedly tyrannical government. Several of the leaders of Geneva’s revolution – such as the banker Etienne Clavière – would figure prominently among those who assumed power in France in the tumultuous years after 1789; others, such as the lawyer François d’Ivernois, would lend their pen to the justification of the Coalitions’ efforts to defeat the anarchical principles of revolutionary France.

In 1787, prominent Swiss officers such as the baron de Besenval warned of the need to increase the pay of the Swiss troops in French service, to keep pace with the rising costs of food in a kingdom under increasingly acute fiscal pressure. If pay increases were withheld, it was not unreasonable to expect that the captains of Swiss companies would sell their offices in order to feed their families, no matter their devotion to the king of France. At the beginning of September 1789, Louis XVI – desperate for military assistance from Switzerland and Germany after the fall of the Bastille in July and the consequential threats to his rule – hastily renewed his alliance with the Catholic cantons in order to ensure that he would not be short of troops. The Swiss themselves were generally royalist in sympathy, and aristocratic and clerical émigrés fleeing France in subsequent years generally found a welcome in Fribourg, Lucerne, and Solothurn.

But sympathy turned to feelings of rage and betrayal after the horrific events of 10 August 1792 in Paris, when over 500 of Louis XVI’s Gardes suisses – one of the élite Swiss regiments in French service – were massacred by the sans-culottes and the French National Guard at the Tuileries. This was after the king had clandestinely surrendered his person and his family to the National Assembly to ensure his and their own safety.

Swiss outrage was directed at the perfidy and treachery of their traditional ally – meaning in this case the French people, as opposed to the hapless king. Anti-French feeling ran high in the Confederacy, while royalist émigrés continued to pour across the frontier to escape the murderous anarchy into which France had descended.

On 20 August 1792, the National Assembly passed a law ending the independence and privileges of the Swiss corps within the service of France, effectively stating that their service was no longer required. François de Barthélemy, recently appointed to the thankless task of ambassador of the French nation to the Swiss Confederacy, frequently underlined the need to satisfy the Swiss demands for continued payment of military pensions and the importation of salt. Otherwise, France would lose entirely its traditional alliance with the Swiss. He also advised the fledging republican government in Paris that it was possible that the leaders of the assorted cantons might decide at the Swiss Federal Diet to rupture the alliance, as a response to the atrocities of 10 August. This would give the Revolution’s enemies – Prussia, Austria, Savoy-Sardinia, and (from January 1793) Great Britain – an opportunity to supplant French pre-eminence and increase their own military recruitment in the Confederacy. This will be discussed further in the second instalment of this post.

John Condren is Research Associate (Geneva case study) for The European Fiscal-Military System project. Email john.condren@history.ox.ac.uk