Our Man in Algiers: A Temporary Fiscal-Military Hub In North Africa, 1707

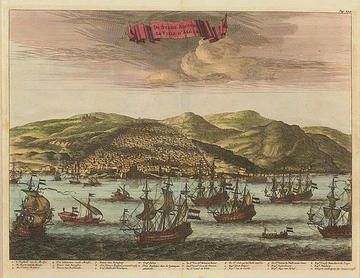

The city of Algiers, c. 1680 (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

In March 1707, the English consul-general in Algiers, Robert Cole, found himself in the middle of a coup. Mohammad Hogga or Bektash ‘and six other resolute Turks’ had captured the palace, dethroned the Dey and taken his place. Cole was rather blasé about the whole affair, perhaps because he had lived in Algiers as a merchant and consul since 1692 and experienced half a dozen coups during this time, and his main concern was what this might mean for England’s influence in this territory.[1] Fortunately he was able to assure his masters in England that all was well, in letters now preserved at the British Library.[2] ‘I am particularly acquainted with five of the seven, who have eaten my bread and plentifully drunk my wine not nine months since’, he said, ‘which I hope will not be forgot when ... our nation may require their assistance in matters of controversy, all being about the Dey in employments of the greatest trust.’ Just to make sure though, he also made a number of presents to the new Dey and those around him, including his son-in-law, and gave a gold watch to a leading figure behind the throne, ‘one of the leading cards, so as long as the government stands, I think it’s well bestowed’.

A Janissary in Algiers, c. 1718 (Nicolas Bonnart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

This diplomacy was vitally necessary because Algiers temporarily occupied a key place in the European fiscal-military system supplying resources for British, Dutch, German and Italian forces fighting the French and Spanish in Spain during the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-13). For much of the eighteenth century Britain tried to cultivate good relations with Algiers and the other Barbary states in North Africa because they were a vital source of provisions for military and naval forces in the Mediterranean, one of the many hubs in a wider set of mercantile networks which moved grain and other provisions around the western Mediterranean. Yet as far as the English government was concerned, these were temporary hubs, of particular importance only in wartime when English forces were present; it was only after the occupation of Gibraltar in 1703 and Minorca in 1710 that they would acquire more permanent importance as friendly sources of supply.[3] No permanent infrastructure was in place, and English forces fighting in the western Mediterranean were therefore forced to lean heavily upon diplomats like Cole – who normally spent their time negotiating ransoms for British ships and sailors captured by Barbary pirates – to make the most of these temporary fiscal-military hubs.

Cole’s relations with the new Dey and his followers were thus of crucial importance, since they allowed him to tap into the provisions flowing through Algiers. ‘By my incessant endeavours with the Dey I have prevailed with him ... to supply the army in Spain with wheat, barley and beans’, he reported, in exchange for supplies of gunpowder. The only problem he faced was a further coup in 1710, ‘arising from the cruelty and insatiable avarice of the late Dey’, who was executed with his son-in-law. Fortunately Cole was able to propriate the new Dey by regifting a gold chain received from the former Dey, ‘and it will likewise be necessary’, he told his masters back in England, ‘to make presents to his chief favourites for the more effectual prevailing in this matter, all my old acquaintances being cut off’. Cole therefore had a vital role while the war lasted, smoothing over diplomatic ruffles and organising the shipment of grain, and demonstrating the real important of temporary hubs such as Algiers in the wider European fiscal-military system in the western Mediterranean.

[1] For Cole, see Colin Heywood, ‘An English merchant and consul-general in Algiers, c. 1676-1712: Robert Cole and his circle’, in Abdeljelil Temimi and Mohamed-Salah Omri (eds), The Movement of people and ideas between Britain and the Maghreb (Zaghouan, 2003) pp. 49-66; J.S. Bromley, ‘A letterbook of Robert Cole, British consul-general at Algiers, 1694-1712’, in idem, Corsairs and Navies, 1660-1760 (London, 1987) pp. 29-42

[2] All quotations are taken from BL, Add MS 61535 ff. 70r-173r

[3] See for example M.S. Anderson, ‘Great Britain and the Barbary states in the eighteenth century’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research 29 (1956) pp. 87-107

Aaron Graham is Research Associate for The European Fiscal-Military System 1530-1870, and focuses on the London case study.