Horses, hay, and hitches in haulage: France’s use of the United Provinces for the movement of military supplies in the Seven Years War

Every major European power faced limits to its wartime ability to provision its forces adequately in the Ancien Régime. The European Fiscal-Military System project investigates these limitations, focusing on networks of suppliers and contractors and analysing the challenges posed by the movement of men and – almost more difficult in early modern Europe – matériel and foodstuffs. Each of us focuses on these questions through the prism of different case-studies: from the transport of iron and timber through the Baltic Sound to the shipment of arms, artillery, and grain along the Danube, the Po, or the Rhine.

In all of these cases, there was a price to pay. Tolls along roads and rivers were a common curse: inspections delayed speedy onward transit to the required destination, and toll-masters and bailiffs could – and frequently did – invent their own rules and regulations in order to squeeze more out of the harassed masters of heavily-laden wagons or riverboats. Even in a monarch’s own territories, challenges of geography, climate, and local restrictions and interests could prove difficult to surmount, as Guy Rowlands has shown in the case of France. It is little wonder that contraband in military supplies and other goods was common. Many of the Swiss and Genevan bankers supplying France with paper money had valuable sidelines in the smuggling of cloth, bullion, and spices across what can loosely be described – in the modern sense – as the French frontier with the Swiss Confederacy. Using the example of a Swiss officer, in the service of France, operating in a neutral country (the United Provinces of the Netherlands), this blog discusses some examples of the difficulties involved in arranging transit.

The French armies campaigning against the Prussians, Hanoverians, and British in northern Germany in the Seven Years War (1756-1763) could not depend upon their homeland to supply all they needed. Therefore, to make up for shortfalls or deficiencies on the part of their own army contractors, Louis XV and his ministers needed the services of a friendly neutral power in the region, where provisions could be purchased and shipped along a sophisticated riverine network, to arrive as close to the relevant theatre of war as realistically possible. The United Provinces’ decision to remain neutral in May 1756 was a blessing: it meant that the French state could avail itself of private Dutch military contractors eager to make a profit out of France’s needs. Moreover, because of a British blockade of French ports, Dutch ships were crucial for the transport to France of essential supplies such as timber and tar from the Baltic. This was despite the energetic protests of the British government, which considered such facilitation of their enemy’s trade as a reckless prolongation of the conflict.

Louis-Auguste-Augustin, comte d’Affry (1713-1793) © Wikimedia Commons

At the end of 1756, Louis XV appointed one of the most distinguished Swiss officers in the French army, Louis-Auguste-Augustin, comte d’Affry, as French ambassador to The Hague. Members of the d’Affry family, from the Swiss Catholic canton of Fribourg, had served the kings of France for over two centuries. The fonds of the d’Affry de Boccard family are conserved at the Archives d’état de Fribourg. A list of d’Affry’s most frequent correspondents during his embassy shows that he maintained regular communication with:

- The commanders and intendant-général of the Army of the Rhine

- The colonel-general of the Swiss and Grison regiments in French service

- The intendant of Hainaut (on France’s frontier with the Austrian Netherlands)

- A horse-supplier (fournisseur de chevaux) for the Army of the Rhine

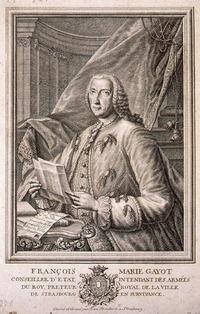

Even this cursory list gives us an idea of the extent of the ambassador’s responsibilities throughout the Seven Years War. One of his principal tasks, as the French king’s representative in a neutral country, was to arrange the transport of essential supplies into Germany – grain, cloth, artillery, bombs, gunpowder, wine for the officers, boots for the soldiers, and so on. For this, he liaised with the intendant-général of the Army of the Lower Rhine, François-Marie Gayot. He also negotiated with the States-General at The Hague to request exemption from tolls and duties for these supplies, as well as passports. D’Affry had other miscellaneous responsibilities: he transmitted (on Gayot’s behalf) bills of exchange to Hamburg, drawn on that city, to pay for the subsistence of prisoners-of-war; and provided to French commanders any information available in The Hague and Amsterdam concerning British naval refitting at Portsmouth.

François-Marie Gayot © Wikimedia Commons

Of all the commodities for which transport was necessary, horses were unsurprisingly the most difficult to move in large numbers: they required stabling or at least grazing, oats and hay, stable-boys to look after them, and access to fresh water. In late 1759, Gayot contracted with a certain M. Schwartz for 500 cavalry remounts to be purchased in Germany and transported to the northern Dutch province of Groningen. Schwartz was then to deliver the horses to the Army of the Rhine’s winter quarters at Roermond, a long way to the south, in the Austrian Netherlands (loosely approximating to modern-day Belgium and Luxembourg). Gayot apologised to D’Affry for his inability to help with transport, thereby leaving to the ambassador the legwork of liaising with Schwartz and asking for the necessary passports from the Dutch authorities. But as 1759 turned to 1760, Schwartz’s requests for more money to meet his unspecified expenses, and his excuses for the horses’ continued failure to arrive at Groningen – mostly weather-related – tested the ambassador’s patience. The horses could only be transported in groups of 80-100 per day, and ice was an obvious deterrent. The passport for their transit was dated 28 February, but it needed the required seals from the admiralty of Amsterdam, meaning that it did not arrive at Groningen in time. The horses finally began to appear in Groningen at the start of March, but the port authorities at Delfzijl charged a toll of six florins per animal on the first consignment of 144 horses, which the desperate Schwartz claimed he could not afford. D’Affry therefore requested the necessary exemption from the States-General on 21 March, as well as the restoration of the duties paid.

Procuring and transporting enough food for horses could also prove complicated. In January 1758, d’Affry received a letter from Gayot with a plea from an entrepreneur of forages for the French army, one Wolff. In April 1757 the bureau at Maastricht had granted Wolff a passport for the transport of forage to the French troops camped at Roermond. This passport would expire after two months. Wolff’s original contract for 200 rations of hay had been reduced to 100 in the meantime, thereby meaning that he had not transported the hay within the time allocated. The Maastricht toll-master had charged him duties on the hay transported between 13 June and 4 July, and Gayot urged d’Affry to have these costs restored to the unfortunate entrepreneur, who had suffered financially through no fault of his own.

D’Affry also had to ensure that entrepreneurs purchasing hay, grain and other supplies in the United Provinces on behalf of the French actually settled their debts. In the spring of 1758 the ambassador was plagued with complaints from two Dutch merchants from Guelders, demanding payment of 20,000 Dutch florins from two of their compatriots who had transported hay for the French cavalry along the Rhine to Wesel (in Germany). Although Gayot and d’Affry ultimately settled the affair, the two Guelders merchants refused to enter into any further arrangement with French buyers unless it was with Gayot himself. D’Affry was irritated at the damage to France’s reputation in the United Provinces, and some three years later he was furious when he realised that Gayot had still not ensured payment to the two Dutch suppliers.

Map of the United Provinces in 1786 © Wikimedia Commons

Fluctuating prices and bans on exports posed their own problems. The province of Holland prohibited exports of forage until 1 July 1758. D’Affry, in a letter to Gayot of 25 May, remarked that this prohibition helped to keep down the price of hay relative to the prices in Utrecht and Guelders, but that the price would reach those levels once the restrictions were lifted. In d’Affry’s words: “the restriction is less a hindrance to the furnishing of our armies than it is a pretext to the enterprisers to maintain their services at the higher price.” D’Affry occasionally signalled a willingness to bend the rules. He explained to Gayot that grain taken along the Meuse to Roermond required only a seal from the admiralty at Rotterdam, but if the same shipment were taken onto the Rhine, it would need approval from the admiralty at Amsterdam: a time-consuming process which d’Affry suggested should be circumvented in the interests of speed. In April 1760 a boatload of 674 barrels of rice was held up at Venlo for several days while d’Affry – rather peremptorily – demanded permission from the States-General for it to be exempted from duties. The transport of goods originating from outside the United Provinces also required passports: such as Gayot’s request to d’Affry that he organise a permit for 8,000 sacks of oats to be taken down the Meuse from Liège to Gennep.

Toll-masters often blocked transports which they deemed illicit or suspicious. For example, in December 1757, a shipment of coin totalling 17,331 Dutch florins was confiscated at the German riverport of Osnabruck, because the authorities doubted its origins: it had been consigned by a Dutch merchant, Henry Hooft, for the French forces in Germany. Ultimately the money was returned to Hooft, though Simon Moses Levy, a Jewish merchant of Amsterdam who had supplied a barrel of silver coin as part of the consignment, later complained that some of his money was missing.

More generally, Jewish involvement in military business was a feature of the period, as my colleague Michael Martoccio has recently shown. D’Affry received propositions in December 1758 from two Portuguese Jewish merchants of Amsterdam, offering grain to the French at favourable prices, though he declined the offer. The significance of widespread Jewish networks in horse-trading across Europe was reflected in a proclamation of 1763 in the d’Affry family’s home city of Fribourg, which accused Jews of trading in poor-quality merchandises and limited their business in the Swiss canton to the buying and selling of horses and cattle.

The Binnenhof at The Hague, meeting-place of the States-General © Wikimedia Commons

Despite being on opposing sides, d’Affry could still request favours from his British counterpart, Joseph Yorke: in November 1759 he asked for a passport for an agent of the French king’s, sent to England to purchase horses for the grande écurie du roi. But issues such as the Dutch willingness to handle French shipments of supplies and artillery were obviously far more sensitive and important, such as in the summer and autumn of 1759, when cannon purchased by the French in Sweden and Denmark was taken to Amsterdam in Dutch ships, for intended onward transport to Dunkerque. As Alice Carter has shown, Yorke’s vociferous protests to the States-General hampered this operation, and caused the Dutch to consider whether their facilitation of both sides was more troublesome than they had expected.

The d’Affry country house at Givisiez, near Fribourg © Wikimedia Commons

This handful of examples demonstrates the challenges which confronted officials trying to ensure speedy movement of supplies in eighteenth-century wars. Even in a region with impressive transport infrastructure, delays and setbacks were the norm rather than the exception. D’Affry’s long career in French service ultimately ended when he escaped from France to Switzerland in October 1792 after the tumultuous and bloody events of that August, when Louis XVI’s Swiss Guards regiment fell victim to the sans-culottes at the Tuileries.

But his role during the Seven Years War as facilitator and organiser of transports of military supplies, in his capacity as a Swiss officer in the service of a foreign monarch and operating within the confines of agreements with a neutral power, serves as a useful exemplar of the research we carry out, and illustrates the transnational complexities of military business in the early modern period.

The archival documents mentioned in this post are from the d’Affry de Boccard collection, at the Archives d’état de Fribourg. I am extremely grateful to M. Guillaume Schmid of the Université de Fribourg for taking the necessary photographs of these letters, and to Professor Claire Gantet and Briony Truscott for helping to arrange this.

Suggested reading:

Carter, Alice Clare, ‘The Dutch as neutrals in the Seven Years War’, in The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 12:3 (1963), pp.818-834.

Czouz-Tornare, Alain-Jacques, Louis d'Affry, 1743-1810 : premier landamman de la Suisse : la Confédération suisse à l'heure napoléonienne (Geneva: Slatkine, 2003)

Félix, Joël, ’Victualling Louis XV’s armies. The munitionnaire des vivres de Flandres et d’Allemagne and the military supply system’ in Richard Harding and Sergio Solbes Ferri (eds.), The Contractor State and its Implications, 1659-1815 (Las Palmas, 2012), pp.99-125.

Lynn, John A. (ed.) Feeding Mars: Logistics in Western Warfare from the Middle Ages to the Present (Boulder, Oxford: Westview Press, 1993)

Morieux, Renaud, The Channel: England, France and the Construction of a Maritime Border in the Eighteenth Century (Cambridge: CUP, 2016).

Prak, Maarten, The Dutch Republic in the Seventeenth Century: The Golden Age (Cambridge: CUP, 2005).

Rowlands, Guy, ‘Moving Mars: the logistical geography of Louis XIV’s France’, in French History, 25:4 (2011), pp.492-514

Scholz, Luca, Borders and Freedom of Movement in the Holy Roman Empire (Oxford: OUP, 2020)

John Condren is Research Associate for The European Fiscal-Military System 1530-1870 and focuses the Geneva case study.