Foreign Enlistment

On 27 February the Foreign Secretary stated she would not oppose, and would even support, British people volunteering for military service in Ukraine1. Her comments appeared to mark a break with current and historical government policy, and have since been hurriedly qualified. After all, repeated efforts have been made over the past decade to criminalise and prosecute people joining ISIS and other terrorist groups in the Middle East and elsewhere, and there were suggestions that those leaving for Ukraine would be liable for prosecution under the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1870. More broadly, such foreign legions would appear to roll back the efforts made since the late nineteenth century to build national armies. Current exceptions, such as the multinational French and Spanish Legions, or the Brigade of Gurkhas in the British Army, as well as the large numbers of foreigners serving in British and American armies, have been dismissed as anachronisms or curiosities, leftovers from the age of imperialism. In fact, foreign manpower has been a key component in British – or English – geostrategic calculations since at least the sixteenth century, as my work from the ERC-funded research project at the University of Oxford, ‘The European Fiscal-Military System, 1530-1870’, has begun to demonstrate.

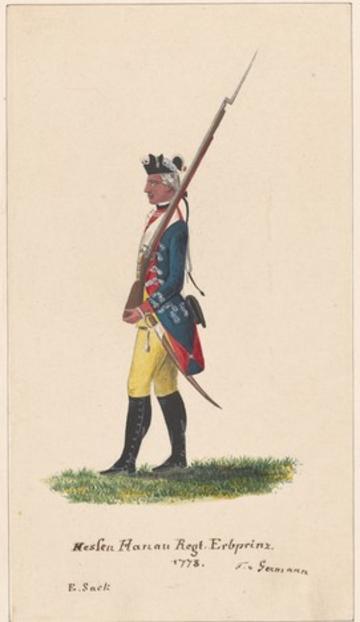

Soldier in the Hessen-Hanau Regiment, 1778. Source: New York Public Library

For a start, English governments repeatedly proved willing to use foreign military manpower at home during the sixteenth century against the various threats – the French, the Scots, the Irish, the Catholics – which Tudor regimes faced. As the British Isles tipped into war between 1637 and 1651, efforts were made by Royalists and Parliamentarians sides to recruit veterans from the Thirty Years War. Some made no secret of their mercenary aims. Captain Carlo Fantom, a Croatian soldier in Parliament’s army, boasted that ‘I care not for your cause: I come to fight for your half-crown[s] and your handsome women’. Others were motivated by loyalty or ideological commitment, in what has been called the last of Britain’s religious wars. From 1688 onwards the British state not only hired contingents of foreign soldiers from allied powers in Europe – such as the infamous Hessian troops, who were not mercenaries, but allied forces subsidised by Britain – but also directly recruited French, German and Swiss Protestants and others for its regiments. Anywhere between 1 and 5 per cent of the British army from the mid-eighteenth century were foreigners, while the 60th Regiment, a direct ancestor of The Rifles, was formed in 1756 specifically for the recruitment of these groups for service in North America.

After 1793 these efforts were taken up a notch with the incorporation into the army of various military refugees from France and its conquests, particularly the armed forces of George III’s possessions as Elector of Hanover, which served as the King’s German Legion after Hanover was occupied by French forces in 1807. At their height in 1813, foreign regiments made up over 10 per cent of the British army, some 32,000 men out of a force numbering around 300,000 in total. Indeed, even in the Crimean War – recently referenced by the Defence Secretary – the British government raised German, Swiss and Italian Legions for service in the Black Sea2.On paper they made up about 15,000 men, along with a further 15,000 supplied by the Kingdom of Savoy and subsidised by Britain, though neither saw service before the end of the war. Many British governments have therefore made extensive use of foreign military manpower in Europe, for their own purposes, even in the era of the modern nation-state and its army of citizens, not to mention the large numbers of locals recruited for service in Britain’s imperial territories as sepoys and askaris.

Secondly, there is an extensive tradition of British service overseas in foreign armies. During the mediaeval period, English condottieri or mercenaries were notorious in Europe, but from the sixteenth century onwards such service has also often been accompanied – and legitimated – by a various degrees of ideological commitment. English and Scottish volunteers served in Dutch armies in the late sixteenth century as the Protestant Dutch fought for separation from Catholic Spain, which recruited many Catholic Irish into its armies. Companies were also raised for service in Europe on both sides during the Thirty Years War (1618-48), seen at the time as a climactic, even apocalyptic, clash between the forces of good and evil. This service was increasingly formalised after 1660. The Dutch Republic maintained for example, between 1672 and 1780 a Scotch Brigade of about 3,000 men, a force technically on loan from the British state but in practice directed and paid by Dutch authorities.

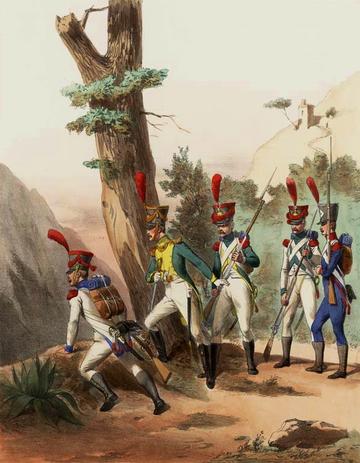

Indeed, large numbers of Catholic Irish – the ‘Wild Geese’ – also served from the late sixteenth century to the early nineteenth century in the Irish brigades run by the French and Spanish governments. The trickle of Irish recruits to these foreign, and enemy, armies was quietly overlooked by the British government, since it was a useful safety valve which removed some of the more vocal and active opponents of British rule in Ireland. Only in wartime, especially after some of those Irish forces were deployed by France to support the Jacobite Rising in Scotland in 1745, did the British government clamp down. The end of the practice arose less from changing views about foreign service and more from the abolition of the Irish Brigade by Revolutionary France in 1793 – though it was revived in 1810 as the Irish Legion – and the gradual opening up of the British army to Irish recruits after 1779, as repeated wars and the lack of foreign recruits placed growing pressures on the British state for manpower.

Officer and soldier of the Irish Legion (second and third from left) c. 1810, from Alfred de Marbot, Régiments étrangers de l'armée napoléonienne, 1810 (1830)

Thirdly, this persisted even after 1815, as European powers began to rearrange themselves into nation-states with armies of citizens, a process still incomplete in 1914. Large numbers of volunteers fought in South America between 1815 and 1825 as territories there asserted their independence from Spain, ranging from Admiral Lord Cochrane, the naval hero, to Sir Gregor MacGregor, a Scottish soldier who had fought in the Peninsular War with the British army, and later ran the infamous ‘Poyais’ financial fraud in 1825. Further groups of volunteers fought for Greek independence in the 1820s, including Lord Byron. Others participated, in smaller numbers, in a range of other conflicts ranging from the American Civil War (1861-5) to the Franco-German War (1870-1) and the Risorgimento in Italy (1870), once again for ideological as well as mercenary reasons. The volunteers who joined both sides of the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s were therefore only the last in a long line of British volunteers allowed to join foreign conflicts for ideological causes.

Though some of these groups were threatened with prosecution for doing so, few prosecutions have ever been begun, let alone resulted in convictions, largely because the Foreign Enlistments Acts have generally been a dead letter. The first was passed in 1819 under pressure from the Spanish government to prevent the flow of volunteers to South America, but since British policy was to promote the independence of these states while also maintaining good relations with Spain, the measure was more of a diplomatic and political gesture than a meaningful act. Indeed, it would be temporarily set aside only two decades later when Spain itself fell into civil war and Britain sought to intervene in the Carlist Wars on the side of the liberal government. It was politically impossible to send British forces – as ministers had done during Portugal’s civil war in the 1820s – not least since France had already sent its own Foreign Legion to support the conservative faction. Instead, to provide a degree of separation and avoid escalating a conflict between superpowers, it was decided to create the British Auxiliary Legion. Paid and commanded by Spanish forces, but organised and recruited from volunteers from the British forces, with the blessing of the British government, the 10,000 men of the Legion helped the liberal Spanish government to defeat their conservative, absolutist opponents in 1839.

Sir Gregor MacGregor, the 'Cacique of Poyais', c. 1820-35. Source: National Portrait Gallery

The intervention by the Foreign Secretary on 27 February therefore forms part of a long, albeit intermittent, tradition of tacit British support for foreign volunteers as the agents of wider British policy, itself often a mixture of realpolitik and genuine ideological commitment. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that was the support of Protestant rebels against the religious and geopolitical threat of Catholic Spain or France. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries this was frequently the support of liberal regimes against their conservative opponents, measures which frequently suited the mood of the general public while also satisfying British economic, political and diplomatic interests. Only when such military service by foreign volunteers posed an active and direct threat to wider British interests and policy – such as pressure from the United States during the American Civil War to cut off aid to the Confederate States – have British ministries taken action, and even then this has often been more symbolic than real. More often, foreign volunteers have been used to do what the government would not or could not do, in support of the causes that the wider public believed in.

1 The Guardian, 28/2/2022, Andrew Sparrow, ‘Liz Truss criticised for back Britons who wish to fight in Ukraine’; The Times, 27/2/2022, Catherine Philp and Oliver Wright, ‘Liz Truss encourages Britons to join Ukraine’s foreign legion’

2 The Times, 24/2/2022, Larisa Brown, ‘We’ll kick Putin’s backside, says Ben Wallace’

Aaron Graham was a Research Associate on The European Fiscal-Military System project between 2019 and 2021, with responsibility for the London case study, and is currently Lecturer in Early Modern British Economic History at University College London.