Privateers from Zeeland to Zealand

Shipping and Shopping

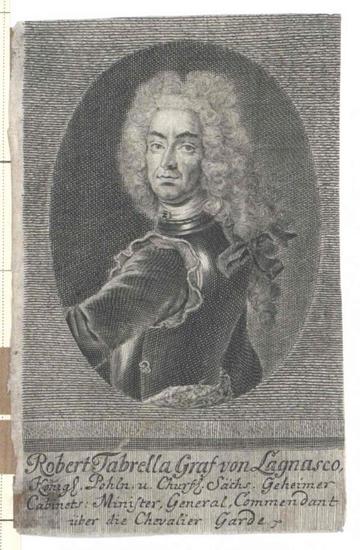

In June 1716, Augustus the Strong (1670-1733) sent his agent, Peter Robert Taparelli, Count of Lagnasco (1659-1735) to the Hague and Amsterdam. The ruler, who was both the Elector of Saxony and the King of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, commissioned Lagnasco to acquire a great variety of things for him. The count’s primary political mission was to explore the types and prices of warships available due to Saxony-Poland’s involvement in the Great Northern War. Nevertheless, the trip became memorable mainly because of the porcelain acquisitions that significantly contributed to the development of August the Strong’s collection, which was enriched with 25,000 new pieces and became the largest of its kind outside Asia by the time of the death of Augustus the Strong. Besides the war vessels and porcelains, the shopping list included various luxury goods: furniture, tapestries, rare and exotic animals, even performing artists who secured their contracts with European courts in the Hague.

Lagnasco, Peter Robert Taparello Graf von - Österreichische Nationalbibliothek - Austrian National Library, Austria - Public Domain

Lagnasco regularly sent letters to Augustus the Strong in which he reported his observations on the price and quality of the products he was expected to buy; he made suggestions about potentially good deals, asked for approvals and further instructions. The most important pieces of his correspondence were published as the appendix of Ruth Sonja Simonis’ study on the most successful aspect of Lagnasco’s quest: the porcelain acquisitions. But even if Lagnasco’s stay in the Hague and his visit to Amsterdam did not yield similarly tangible results in terms of the acquisition of war assets, his letters give precise account of the careful monitoring both of the diplomatic manoeuvres of the great powers of Europe and the international market of fiscal-military resources. The latter ones had to be explored, calculated with and secured before actual armed conflicts broke out. At the same time, the demand for troops, ships, military experts, etc. largely depended on diplomatic affairs. Finding out the intentions of potential allies and enemies was crucial and using informal channels could be sometimes quicker and more reliable than the reports of official envoys and ambassadors. Thus, being a regular customer at the market of luxury goods and scientific curiosities in the Netherlands could serve multiple purposes: the auctions and other events enabled contacts with potential informants and tested a ruler’s capacity to cover large expenses, to transfer significant sums in a short period of time and to establish business relations in transportation and logistics.

Count Lagnasco’s correspondence provides insight into a world in which the exchange of luxury goods was interconnected with the flow of information on military affairs and international diplomatic relations.

Augustus the Strong and the Great Northern War

Why did Augustus the Strong need war vessels? As the king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, he was involved in the Great Northern War (1700–1721) as member of the anti-Swedish alliance led by the Russian tsar, Peter the Great. The alliance also included Frederick IV, the king of Denmark and Norway, Frederick William I, the king of Prussia and elector of Brandenburg and George I from the House of Hanover, who became the king of Great Britain in 1714. Whilst limiting Swedish hegemony was the common interest of these monarchs, the rapid expansion of Russia was also concerning for them and often hindered their cooperation.

Augustus the Strong’s position as the king of Poland-Lithuania was supported by Russia against the favoured candidate of Sweden, Stanisław Leszczyński, who reigned in Poland between 1704–1709 as Stanislaw I. After Sweden was defeated in the Battle of Poltava in 1709, Russia extended its supremacy over the South-Eastern coast of the Baltic. This included mainly former Swedish provinces surrounding St. Petersburg/Gulf of Finland (parts of Karelia, Ingria) and the Gulf of Riga (Livonia, Estonia, the formally Polish-Lithuanian vassal Courland, Saaremaa/Ösel).

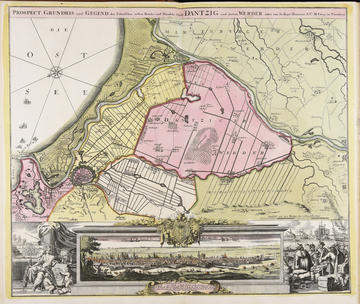

Danzig/ Gdańsk, ca, 1720, Wikimedia Commons

In 1716, Peter the Great was busy mobilizing the resources of his allies for an attack on Scania, the southern part of Sweden. He mainly relied on the naval force of Denmark and he eagerly tried to involve Great Britain, too, as the Russian fleet was not strong enough yet. Expanding Russian influence further to the west on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, the most significant city was Gdańsk/Danzig, enjoying a special status and great autonomy as part of Poland. Gdańsk was primarily a merchant city, with no navy, but it played a significant role in securing provisions and supplying armies with grain. At that time, Sweden was still an important trading partner of Gdańsk – a highly frustrating factor for Peter the Great, who wanted to cut his enemy off from the food supplies arriving from the Baltic. The city’s proximity to Mecklenburg and Pommern also made it a place where armies passing through could be garrisoned. Before 1709, this could include Swedish troops, later Russian, Saxon, Polish, Prussian armies were stationed around the city. Due to its strategical significance, Peter the Great demanded on 2 May 1716 that Gdańsk should stop any kind of communication and trade with Sweden and provide four privateering ships (Capern), equipped with 12 guns and 50 men or pay 200 thaler for the acquisition and equipment of the ships and cover the expenses of the later payment and provisioning of the personnel. The king of Poland was expected to assert his royal power over the city and enforce the fulfilment of Peter the Great’s requirements. On 9th May the City Council of Gdańsk issued a declaration in which it promised to stop trading with Sweden and to provide the four ships. The only point in which the declaration deviated from the tsar’s demands was the question of personnel: Peter the Great wanted to use his own subjects, while the city promised to recruit the sailors from Poland and add Russian personnel only with the king’s consent. The city started building the vessels and, at the same time, petitioned for the king’s patronage over the war vessels. The Council of Gdańsk paid the ruler 100,000 florins in order to gain his support.

Privateers in the Service of August II the Strong

Whether Augustus the Strong wanted to invest the aforementioned sum to get ships in the Netherlands is unclear, but it is noteworthy that the building costs of the four ships were also estimated to be 100,000 florins, while the service pay and provisioning of the personnel was expected to be approximately 2800 thaler. It is likely that the ruler wanted to consider the costs of building and maintaining warships in comparison with the price of privateers hired only for the duration of the military actions planned. It could have been also quicker than building entirely new ships. He was not inexperienced in or lacking the ambition to create a privateering fleet of his own. In 1700, he bought four merchant vessels in Lübeck, adapted them to privateering and used them mainly against Swedish ships. This short-lived attempt ended in 1701-1702 when Swedish forces destroyed the ships and the countries interested in Baltic trade protested against this practice in Warsaw. In 1713, the Saxon General Commissariat rented a merchant ship in Elblag on behalf of Augustus the Strong and converted it into a privateer in order to protect the supplies transported to Saxon troops in Pomerania. The two Danish commanders of the ship, Captain Hans Agaisson and skipper Johann Forbes, got into conflict with the merchants of Gdańsk when they also attacked ships of the city sailing for Sweden. Such actions transgressed the tasks described in the letter of marque issued by the ruler, who ordered the return of the ship to Elblag, where the merchants could claim compensation for their losses.

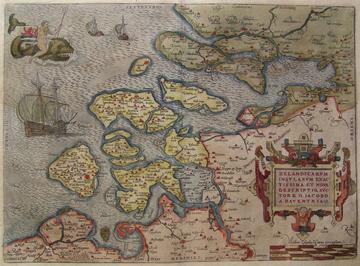

The County of Zeeland in 1580; Ortelius naar v Deventer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1716, for those wanting to hire privateers and find the expertise necessary for building up and managing a navy, the Netherlands was the right place to go. Count Lagnasco left for the Hague shortly after the tsar’s requirements became clear. On 4 July 1716, he reported that he was waiting for a response from Zeeland, where he found the type of armed ships August the Strong required. “As for the man trained in the construction of ships and in the regulations and discipline of the navy, I believe that I have already found him as your majesty requires. He could be useful to us at the same time in dealing and concluding with the shipowners.” Lagnasco remained secretive in his letters and he did not disclose the names of the people whom he negotiated with. His reference to Zeeland – a province of the Netherlands with a history of privateering and piracy from the late sixteenth century – and his later letters make it clear that he did not intend buying ships as properties, but he tried to hire privateers whose activity easily blended into piracy. He noted that “in order to better encourage these shipowners to make catches, it will be necessary to promise them in the treaty which we will have with them, a certain sum for each canon and each soldier which they will find on the armed vessels, of which they will have made themselves masters.” Lagnasco asked for precise instructions from the ruler how to proceed. The answer is not known, but, in his letter written on 28 July, he referred to copies both of his own letter sent to Zeeland and the response he received. Unfortunately, these copies were not preserved, but a short summary of their content in Lagnasco’s letter informs that the shipowners were willing to make a deal and to send a delegate to the Hague to make a draft of a treaty. Lagnasco waited for this person to hear their proposals that he intended to send to Augustus the Strong to clarify if it was really in accordance with his intention and interests. On 15 August, Lagnasco attached another document, containing the claims of the Zeeland shipowners. Unfortunately, this document was not preserved either and all that can be known about it is that its conditions for providing four armed and equipped ships were considered unacceptable. Lagnasco did not even find the proposal worth responding to until the shipowners got back to him with more reasonable claims. At the same time, he admitted to August the Strong that the reasoning of the ship owners was rational. The potential booty gained from capturing Swedish ships was not particularly attractive: the Swedes had no merchant ships at sea and, even if they did, the cargo was not too valuable. At the same time, attacking a warship was risky and the shipowners were cautious not to manoeuvre themselves into a situation in which “only blows could be gained”. Despite these considerations, Lagnasco still found the claims exorbitant and he added that the campaigning season was already so advanced that by the time the four ships were armed and equipped, there would be only a very short period of time during which they could be deployed or, due to the winter, they could not be used at all until next spring.

There is no evidence of any deal made between Augustus the Strong and the shipowners of Zeeland. Whilst the negotiations were going on in the Hague, the ship-building project progressed in Gdańsk fairly quickly, as the city had been an important ship-building centre. The shipowners and merchants, Benjamin Blech and Benedict Schmidt were commissioned to build the vessels on 26 May and the first two ships were ready to sail by August. Nevertheless, it is unclear whether only three or all four ships were built in the end. Their deployment was definitely postponed.

Withdrawal from military actions – back to shopping

'The seat of war in ye North: or a map of the Baltick, with part of the North Sea' by H. Moll, London, 1717 (Norman B. Leventhal Map Center)

By September 1716, Prussian, Danish, Russian, British and Dutch troops and 67 warships were ready to attack Sweden. They had been concentrated in the Danish territory of Zealand, but at the last minute, Peter the Great cancelled the invasion of Scania. He found the timing too late and the naval forces too weak without the support of Great Britain. During the winter 1716/1717 he himself travelled to the Netherlands and planned to meet George I, who happened to be in Hanover, managing the affairs of his Electorate and who was supposed to pass through the Netherlands on his way back to England. Nevertheless, George I still tried to avoid the involvement of his navy in the military actions proposed by Russia. In the end he did not go to Holland and, being already on board at Vlaardingen, he refused to meet the tsar by referring to the unfavourable weather conditions and he departed a few days later without meeting him. Shortly after his arrival on 1 February 1717, a plot against the English throne was discovered and a Swedish diplomat, baron Görtz was identified as the mastermind behind it. Russia’s suspected involvement made the relations of the two rulers even more alienated. The tsar returned to Amsterdam and made the best out of his time there: he continued exploring the latest scientific and technical inventions in the Dutch Republic and purchased artworks.

Sources:

Simonis, Ruth Sonja. ‘Transcriptions’. In Microstructures of Global Trade Porcelain Acquisitions through Private Networks for Augustus the Strong, 95–287. Dresden, 2020. https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.499.

Jubilaeum Theatri Europaei ... Oder Außführlich Fortgeführte Freidens- Und Kriegs-Beschreibung: Und Was Mehr von Denck- Und Und Merckwürdigsten Geschichten in Europa ... Und Auch Einigen in Den Übrigen Welt- Theilen: Zu Wasser Und Lande, Vom 1716ten Jahr, Biß Zu Ausgang Des 1718ten Jahren Fortgegangen. Frankfurt am Main, 1738. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=hO-YLgYiS0gC.

Literature:

Knoppers, Jake V. Th. ‘The Visits of Peter the Great to the United Provinces in 1697-98 and 1716-17 as Seen in Light of the Dutch Sources’. McGill University, 1969. https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/dn39x276p.

Loo, I.J. van. ‘Organising and Financing Zeeland Privateering, 1598-1609’. Leidschrift: The Republic’s Money 13 (2019): 68–95.

Lunsford, V. Piracy and Privateering in the Golden Age Netherlands. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Margócsy, Dániel. ‘Peter the Great on a Shopping Spree’. In Commercial Visions: Science, Trade, and Visual Culture in the Dutch Golden Age, 198–216. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Simonis, Ruth Sonja. Microstructures of Global Trade Porcelain Acquisitions through Private Networks for Augustus the Strong. Dresden, 2020. https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.499.

Trzoska, Jerzy. ‘Der Streit Zwischen Dem Sachsen August II. Und Peter I. Und Die Kaperschiffe von Gdańsk (1716-1721)’. Studia Maritima 6 (1987): 81–104.

Trzoska, Jerzy. ‘Naval Forces and Sea-Borne Trade in Augustus II’s Policy’. Acta Poloniae Historica 75 (1997): 85–100.

Trzoska, Jerzy, and Małgorzata Osiewicz-Maternowska. ‘Danziger Handel und Schifffahrt angesichts der Veränderungen im Europäischen Machtsystem während des Grossen Nordischen Krieges’. Studia Maritima 24 (2011): 63–86.

Katalin Pataki is Research Associate for the Vienna case study for The European Fiscal-Military System 1530-1870.